Background

The shoulder is a ball and socket joint. The bony socket is very shallow and the ball quite large. This allows a very wide range of movement in the normal situation, more so than any other joint in the body. This arrangement is inherently unstable. The stability to the ball in the socket comes from short muscles which attach around the margin of the ball, and by a strong fibrous bag called the joint capsule. This capsule does not stretch. To achieve a full range of shoulder movement there has some looseness of the capsule to allow movement.

Frozen shoulder, also known as adhesive capsulitis is a condition that causes thickening and contracture of the joint capsule. The condition is most common in the 45 to 65 year age group. At any time it may affect 2-5% of the general population. It is four times more common in diabetics. The underlying cause of this condition is not well understood. It may come out of the blue, or it may be associated with other medical conditions. The common thread amongst these conditions is a period of relative immobility of the shoulder. Diabetics, for reasons that are not understood, seem to have a more aggressive form of this condition and in fact the condition is more frequently found in these people.

Frozen shoulder is not a form of arthritis. In general the end point of frozen shoulder in fact is normal shoulder. Frozen shoulder may co-exist with wear and tear arthritis in the joint or even rotator cuff tear but, at the end of the day, it will come and it will go, leaving the shoulder in the same condition at the time it started, perhaps with a small element of stiffness.

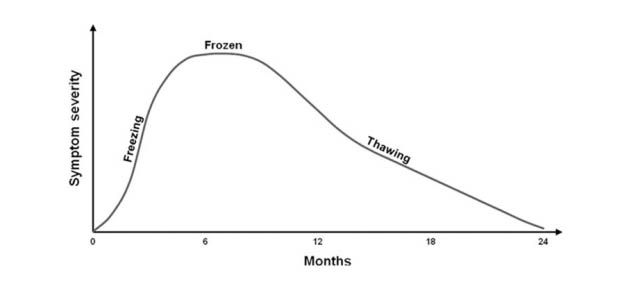

Frozen shoulder rarely affects both shoulders at the same time although one in five may experience trouble with the other shoulder at some time in the future. There are defined stages in the development and resolution of frozen shoulder. Typically the disease lasts for 1-3.5 years:

- Initially the shoulder joint capsule becomes inflamed and there is a progressive increase in pain. As the capsule is stretched with movement towards the end of range the pain can be excruciating. (roughly 10-34 weeks)

- This progresses to stiffness which seems to slowly increase over a period of some months. Patients typically are aware of pain on reaching. Common examples include reaching to the back seat of the car, dressing, reaching for a wallet from the back pocket or attempting to do up a bra. Rapid, unexpected movement of the shoulder may also provoke severe pain. (4-12 months)

- Eventually the pain, and then the stiffness, resolve – this is the thawing phase (6 months)

Treatment

Frozen shoulder, if untreated, may last up to two and a three years with up to 70% of patients are left with some restriction of movement. In 10 to 15%, this restriction of movement will result in a long term functional problem.

Injection

Frozen Shoulder is painful as it improves. In order to make the best progress it is necessary to push the range of motion of the shoulder into the painful region on a regular basis. To assist with this the first step is to organise an x-ray controlled injection of the shoulder joint itself with cortisone. This will give you dramatic but temporary relief for a few weeks.

This is a graph representing the progress of pain and stiffness in the untreated shoulder.

Continuum of Phases in Adhesive Capsulitis. Hsu, et al. Current review of Adhesive Capsulitis. JSES, 20;502-514, 2011.

Physiotherapy

During this period it is best to push hard towards a normal range of motion and stretch the shoulder at every opportunity in daily activity. In addition to thisyou will be given a formal stretching exercise program which will be supervised by a physiotherapist. Stretching techniques are important and the way to make ground in fact is to push to only 80% of the pain that you can tolerate and maintain the stretch against the end of the range for as long as possible. Ideally you should set up three or four sessions per day where you spend a few minutes working into the end of the range in all directions.

It is very important to discuss your progress and daily pain experience with your shoulder therapist, initially once a week but, depending on progress, sessions it may only be necessary once a month. Paradoxically patients frequently describe dramatic improvement in their level of pain and function within a few weeks after the start of this fairly aggressive treatment program in combination with a steroid injection.

This combination treatment can dramatically shorten the overall convalescence and lead more reliably to a normal shoulder. The most important part of your treatment is to understand that you should continue to push into the painful part of shoulder motion in spite of pain. Doing so will not result in any structural damage to the shoulder, but rather will help bit-by-bit regain the range of motion as you push into the end of the range of motion in daily activity. The worst thing that you can do is protect the shoulder by treating the arm as a “broken wing”. Movement is the most important thing.

Surgery

Occasionally a combination of injections and physiotherapy does not get on top of the pain and stiffness associated with a frozen shoulder. In these cases surgery performed under general anesthetic can help to break down some of the adhesions and scar tissue around the shoulder joint. This is achieved with a forced manipulation of the shoulder in combination with a arthroscopic or ‘key hole’ release of some of the tight capsule.

This procedure is generally performed as a day case, with an overnight stay in hospital. A formal physiotherapy program is conducted after the procedure. A sling is generally not required after the procedure.